DREAM SONG 1 Huffy Henry hid the day, unappeasable Henry sulked. I see his point,—a trying to put things over. It was the thought that they thought they could do it made Henry wicked & away. But he should have come out and talked. All the world like a woolen lover once did seem on Henry’s side. Then came a departure. Thereafter nothing fell out as it might or ought. I don’t see how Henry, pried open for all the world to see, survived. What he has now to say is a long wonder the world can bear & be. Once in a sycamore I was glad all at the top, and I sang. Hard on the land wears the strong sea and empty grows every bed.

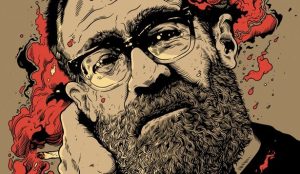

As I prepare to teach a course on ‘Depression in Literature’ in the coming term at SAS, I’ve been revisiting some American confessional poetry that I enjoyed in my undergraduate days. I once wrote an undergraduate essay on John Berryman, who jumped off the Washington Avenue Bridge in Minneapolis in January 1972 after years of suffering from depression and alcoholism.

He’s primarily known for The Dream Songs, the first of which I think references the infant ego’s experience of becoming differentiated from the external world. ‘Henry’ is the main character in The Dream Songs and I take him to be an unintegrated part of the poet’s psyche that is still experiencing this original wound.

What’s interesting in the context of the ‘material relations’ blog is the “woolen lover” of stanza two, which I think is a teddy bear Henry/Berryman had in childhood.

Perhaps the key line is at the start of the third stanza: “What he has now to say is a long wonder the world can bear & be.” The “woolen lover” is never explicitly stated to be a bear, and the “bear” in this line is apparently a verb. The relation between them is highly equivocal, but I fancy that in the poem’s dream logic there’s a hidden connection and that this ‘bear’ still refers to his toy: the world remains his teddy bear and his “wonder” that it can “bear and be” encodes his astonishment that a narcissistic love object now exists as something transcendent to him and is indifferent to his needs. Or am I reading too much into it?

Although not mentioned here, Berryman’s father’s suicide when he was a child is part of the process by which the world he once felt in loving harmony with becomes a stranger to him. Berryman often flirts with self-indulgence as he dramatises his adult immaturity, but in this poem I think he successfully infuses an account of sentimental attachment to a stuffed toy with a sense of theological loss that one can imagine being a consequence of losing your father in this way. He was perhaps influenced by Freud’s belief that mystical experience and the “primitive ego-feeling” of the infant are much the same thing, or perhaps he just illustrates how for some people they can be the same thing.

This recording of Berryman reading the poem is quite good, though he sounds drunk. He usually was.